Para leer en español, haga clic aquí.

In recent months, Peru has been thrown into turmoil after social upheavals that led to at least 70 deaths. The unrest has directly impacted the tourism sector through the dramatic and damaging closure of Machu Picchu. But what hasn’t been picked up by the international media is the passing of a controversial new law for porters working on the classic Inca Trail to Machu Picchu. Amid all this upheaval, there might be a sustainable solution to at least some of the problems that still plague one of the most famous hikes in the world. And llamas are part of this plan…

Peru erupts in civil unrest, and tourism comes to a standstill

Since early December 2022, a political power vacuum has consumed Peru, leading to social upheavals across the rural hinterlands. Violence and road blockades have resulted in more than 70 deaths, paralyzed regional economies, and given a big black eye to Peru’s international image of safety and stability. The unrest was driven by a myriad of agendas, some opaque from Narcos, illegal miners and Andean populists from Bolivia. But these interest were acting alongside and in concert with authentic and much needed calls from indigeneous communities for an equal place in society. The deep-seated sense of resentment and economic vulnerability among Andean populations was like tinder to a fire.

The impact on tourism has been disastrous, with estimates reaching US$600 million in losses in the first quarter of 2023 due to the closure of Machu Picchu and roadblocks across the Cusco region. What hurt even more is that the divisionism hawked by those looking to fill the vacuum of a deposed president used Andean identity politics to fight for their cause – attempting to put wedge between tourism outfitters and indigeneous communities in and around Cusco whom they work with. For those of us in tourism, it was as if the indigenous lifestyles and cultural patrimony we promote to the world acted in self-harm, making a kamikaze mission of sorts straight to the heart of Peru’s tourism sector. How do we explain this? And, more importantly, what can be done to avoid a repeat?

It’s important to mention that most of the workers in Cusco’s tourism sector did not favor the form or demands of the protests. What is critical, though, is that the imagery of a closed Machu Picchu, and even a small group of traditionally dressed picketing campesinos, was powerful. It was as if a century of glossy tourism brochures to Machu Picchu had turned dark. The manipulations behind the various agendas of the unrest, knew precisely the symbolism they needed grab national and global attention, and harnessed the resentment and general feeling of unfairness in Peru’s rural areas for their purpose.

A brief social and economic history of the Inca Trail, its porters, and your author

Almost 18 years ago to the day, I arrived in the Sacred Valley to volunteer with an NGO working in the field of porters’ rights. It was a small organization of less than a half dozen twenty-somethings, primarily from universities in Europe and the United States. My stint was brief but profoundly transformative. I had spent the first half of my twenties in the service industry in one of the most affluent communities on the planet in California. Suddenly, I was immersed in the indigenous communities of the high Andes, learning about a service of another type: that of indigenous labor on the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu.

Five years later, after becoming a naturalized Peruvian citizen, I founded a tour operator that promoted and brought travelers to hike the famed classic Inca Trail to Machu Picchu. Anyone selling Peru tourism in the early 2010s was marketing Machu Picchu alongside some sort of trekking experience to get there. Over the previous decade, basic regulations had been established regarding minimum pay, age, load limits for porters, and a host of requirements such as waste. The Inca Trail brand grew in strength during those years. Demand easily exceeded the regulated supply of 250 hikers per day, and hikers overflowed onto nearby routes like Salkantay. The tour operator I founded, SA Expeditions, now sends travelers across the globe, but we very much owe our early beginnings to marketing some form of the “Inca Trail brand” on today’s digital platforms.

Ten years after my initial immersion to the Andes, I decided to dive further into the topic, leading a multi-year effort to explore the Great Inca Road 2,000 miles down the spine of the Andes, starting in Cuenca, Ecuador and ending in Cusco, Peru. We trekked for 130 continuous days, supported by a llama caravan and a team of porters who would otherwise have spent the season working on the classic Inca Trail to Machu Picchu.

That expedition was born out of my curiosity in the Incas. While I had outgrown the crowds and accessibility of the trails around Cusco, I appreciated the economic activity and employment they brought and the positive impact they were having on visitors. I needed to better understand the depth of Inca trails and their role in what was the most advanced society in pre-European South America. And doing so with llamas and my indigenous colleagues would help me understand how these native animals, supported with indigenous knowledge, could help modernize trekking in the Cusco region and make it more sustainable.

This continued reliance of Machu Picchu for the country’s tourism industry to exist, which is only one of countless Inca sites atop a Peruvian mountain, is environmentally and socio-economically unsustainable – as we have all been harshly reminded over the past 90 days while Machu Picchu was closed.

Section Type: standardWidthImageS

Group of llamas on the Great Inca Trail in northern Peru. The llamas carried the bulk of the gear for 130 days during the author's expedition from Cuenca, Ecuador to Cusco, Peru.

A surprising and strange porter law comes about

Just before the leftist president was ousted, clandestine political operatives pushed through a new porter law with no consultation from the main porter union nor the companies that had built the Inca Trail industry over the past 30 years. The law, which increased porter pay, also implied that porters had to be formal employees, as if they we’re working in an office building in Lima. In the local context this implies limiting the porters’ ability to work with multiple agencies and placed limits on the days and hours they would be allowed to work on the Inca Trail (no organization, government or otherwise, has been able to clearly define how to implement the new law in practice). Anyone with even a light understanding of how porters balance work on the Inca Trail with more traditional forms of work in agriculture and community would realize that this rigid, Western form of thought does not make sense in the local Andean context.

It’s almost like it was written by a Western NGO with good intentions, yet served up to make implementation of the law nearly impossible to manage in practice. What the law did do, though, is set a political trap, making it difficult for anyone who acknowledged the need to improve porter pay and conditions to oppose the law. Furthermore, it has been used to alienate and divide indigenous communities from the tourism outfitters they’d partnered with to build adventure tourism in the region.

Registered operators on the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu and involved in the country’s main tourism unions are now working to pause and revise the law. Any casual observer with access to this process would quickly realize that increases in porter pay are not a sticking point. Most operators believe a pay increase is needed – with or without the new law, which is being challenged in court with nuanced support by the porter union, and the travel outfitters who are funding the efforts.

Section Type: standardWidthImageS

Porters on the classic Inca Trail to Machu Picchu. In recent years, the maximum carrying weight for a porter is 44 lbs. (Photo: Chris Feser, Wikimedia Commons)

Building high-value economic opportunities that also benefit the planet

As our industry and its many partners work together to find a solution to the uncertainty surrounding the new porter law #31614 as created, I couldn’t help but think back to the llamas that accompanied our team across the Great Inca Road.

Here’s a quick 101 on how llamas work in their native ecosystems… Llamas’ feet are like dogs’ paws, meaning they don’t tear apart 600-year-old Inca trails in the same way that hoofed animals from Europe do. What’s more, they nibble the tender tops of grasses, preserving the roots below – hoofed animals rip plants out roots and all. This, coupled with the value of llama dung as fertilizer, is critical to restoring the sensitive Andean habitats that have been destroyed by overgrazing of hoofed animals since the arrival of Europeans. The cultural identity of the Andes was always inextricably linked to using llamas as tools for cargo and transportation, and bringing these animals back will only strengthen traditional practices and the identity of the indigenous populations. Even the Inca trails built during the 15th century were as much for llamas as they were for humans. Today, 99% of all tourism in Cusco that uses animals for cargo, uses European hoofed animals.

And today, in 2023, to prevent damage to the most famed and environmentally and culturally sensitive Inca Trail to Machu Picchu, our industry uses indigenous labor to carry all sorts of accessories of comfort for Western visitors! It’s time that we move into the future by reviving the past. The Inca Trail, and all other commercial Inca trails in Peru, should be working to reestablish the use of llamas for cargo: not humans and ideally less use of hoofed animals. Efforts to make this happen need to increase in pace, as the environmental sustainability of the trails and the social agreement between indigenous communities and tourism, will depend on it.

Bringing back llamas on the Inca Trail could spread capacity building of small-scale llama breeding across thousands of indigenous families in the Cusco region. It would also increase the value visitors would get from hiking with llamas, both because of the cool factor and because they would get a more authentic insight into Andean culture. Most importantly, using thousands of llamas as animals of cargo would create a massive economic opportunity for local populations. The forty or so pounds carried by a llama, is similar to the weight carried by a porter, which means we would need a similar amount to support loads on the Inca Trail. If rules were put in place to avoid monopolies providing the llama power, it would incentivize the porters and their communities to breed llamas for trekking, and it would also allow them to pivot from being porteros to llameros (llama handlers) for the hundreds of thousands of tourists who come trekking in the Andes every year.

Section Type: standardWidthImageS

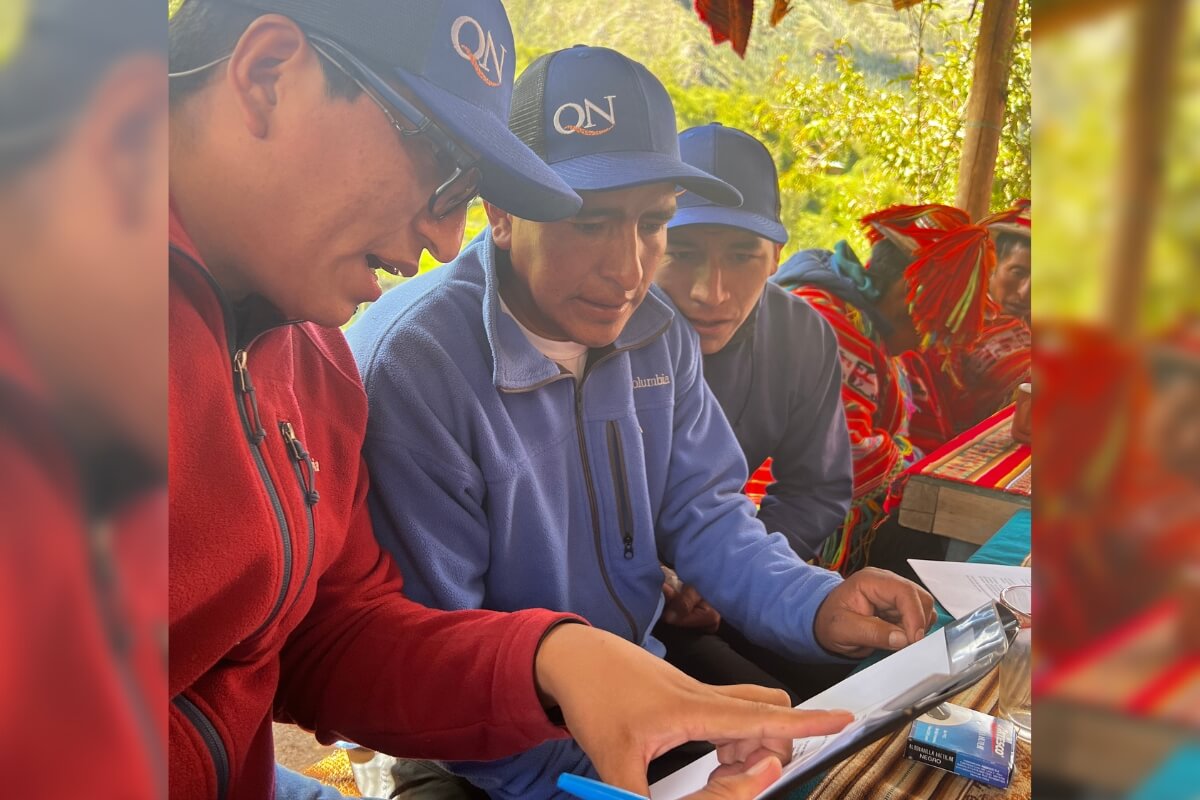

Flavio Paucar, a cook on the Inca Trail, reviews his work contract including increased pay and benefits while working on the trail.

A short-term solution that keeps the long-term goal in view

Right now, to preserve jobs and to continue to reactivate Peru’s tourism sector from the pandemic, we need to find a short-term solution by modifying and clarifying the porter law. We need to be pragmatic in our actions based on today’s realities, and take action that is human-centered and within the local context. Aspiring politicians and foreign NGOs often do not have the local economy and jobs at the center of their agendas.

Until we find a long-term solution to using humans as porters, we need to increase porters’ pay and ensure they have the equipment necessary to be dry, warm, and comfortable while they sleep and work on the trail. We need to learn from the experience of companies that have been leading the Inca Trail economy and welfare of porter communities over past decades.

At the same time, we need to diversify how we promote the term/brand “Inca Trail” in source markets to capitalize on the full demand (not just 250 trekkers on the classic version) of those interested to know the Inca Trail. Lastly, but so importantly, we need to be wary of operator monopolies on the classic Inca Trail to increase competition and expand porter options and choices when deciding which firm(s) they want to work with.

We need to become more sustainable and diversified as an industry. Our profits, the jobs we create, and the communities that we strengthen require it. Llamas can and should be a part of that solution.

Section Type: standardWidthImageS

SA Expeditions outfitter for the classic Inca Trail, takes a picture with the porter team at the end of their meeting to establish commitments between both sides.

Copyright © 2025 SA Luxury Expeditions LLC, All rights reserved | 95 Third Street, 2nd floor, San Francisco, CA, 94103 | 415-549-8049

California Registered Seller of Travel - CST 2115890-50. Registration as a seller of travel does not constitute approval by the state of California.