India’s space program has been around for more than 70 years. And it’s only just getting going. Tourist flights are on the horizon…

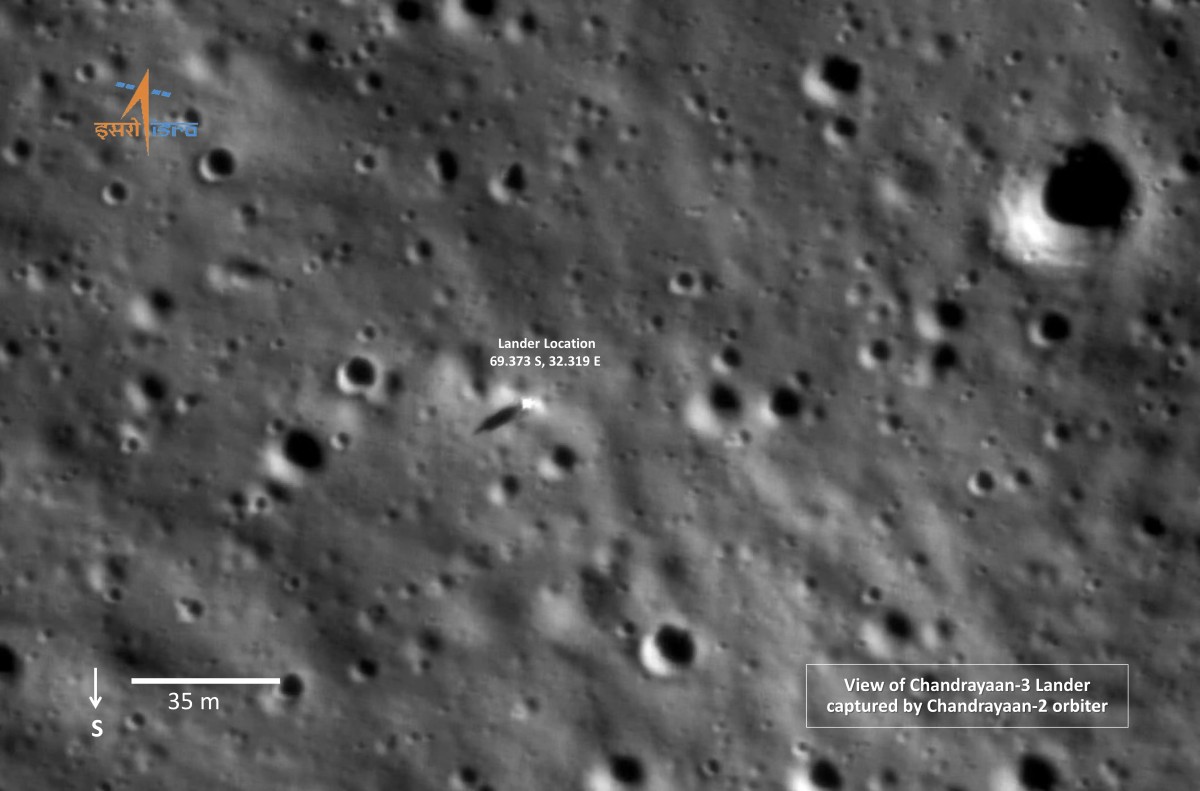

I will admit to being surprised, in August 2023, when I saw on CNN that India had successfully landed a spacecraft on the moon. It was just the fourth nation to achieve the feat, and it was done on a shoestring budget – the project cost $80 million, compared to the $175 million Christopher Nolan spent making the Hollywood space epic Interstellar.

Before then, I wasn’t even aware that India even had a space program, let alone the ability to pull off a moon landing – and I don’t think I was alone.

Section Type: standardWidthImageS

Image of Chandrayaan-3 Lander captured by OHRC camera aboard Chandrayaan-2 (Photo: ISRO)

Even more remarkable was the fact that, in the words of the Economist, “India did not just land its robot on the moon. It did it with style … The poise with which Chandrayaan-3’s ‘automatic landing sequence’ brought the spacecraft down onto the moon’s surface was striking. The spacecraft’s trajectory dropped smoothly from thousands of kilometers an hour to a walking pace, before a last little cheeky hover as the system checked the landing site and then settled itself down onto the lunar surface.”

Turns out my surprise was entirely unwarranted. India has had a formal space program since 1962 – and a fascination with rockets that dates back to the 1700s. Read on for a crash course…

Tipu Sultan and the world’s first war rockets

Tipu Sultan, the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore in southern India between 1782 and 1799, is credited as the pioneer of modern war rockets. While rockets had been used in China since the 13th century, Tipu Sultan was the first to use iron casings (before then rocket casings were typically made from bamboo or paper and resembled modern fireworks).

Iron-cased Mysorean rockets didn’t just fly farther than their predecessors – they were also more accurate and far deadlier. Brigades of 200 rocket men would launch rockets with unerring precision, while wheeled rocket launchers could fire up to 10 rockets simultaneously. Rockets were used to devastating effect in several wars against the British, perhaps most notably during the Battle of Sultanpet Tope in April 1799. A young English officer, Bayly, wrote:

“So pestered were we with the rocket boys that there was no moving without danger from the destructive missiles. The rockets and musketry from 20,000 of the enemy were incessant. No hail could be thicker. Every illumination of blue lights was accompanied by a shower of rockets, some of which entered the head of the column, passing through to the rear, causing death, wounds, and dreadful lacerations from the long bamboos of 20 or 30 feet, which are invariably attached to them.”

Section Type: standardWidthImageS

Illustration of the East India Company confrontation with Mysorean rockets at the Battle of Guntur, 1780

When the British eventually defeated the Mysoreans, they seized thousands of unused rockets. Samples taken back to Britain were used by Sir William Congreve to develop the Congreve Rocket – used during both the Napoleonic Wars and the Battle of Baltimore, and mentioned in the Star-Spangled Banner.

Stephen Smith’s airmail rockets

In the early 20th century, the Indian Himalayas were the unlikely setting for pioneering experiments with so-called “airmail rockets”. Between 1934 and 1944, Stephen H Smith – the only son of a tea plantation manager from Norfolk in England – successfully used rockets to deliver letters, food, medicine, and even live animals. On 29 June 1935, one of his rockets carried a rooster and a hen across the River Damodar. Both animals survived the flight and lived out their days in a zoo in Calcutta.

Rocket mail never really took off (pun intended) but it was once taken seriously in the United States, Austria, and Germany. Smith’s American contemporary, Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield, predicted that “before man reaches the moon, mail will be delivered within hours from New York to California, to Britain, to India, or Australia by guided missiles.” Summerfield may have been proved wrong, but there’s no denying people like Smith paved the way for the use of rockets and missiles to deliver payloads of all kinds – including humans.

Section Type: standardWidthImageS

A commemorative postage stamp on ‘rocket mail’ with a portrait of Stephen Smith (Photo: Government of India)

The launch of India’s space program

The space race between America and the Soviet Union kicked off in 1957 with the launch of Sputnik. Just five years later, independent India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, launched the Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR) later renamed the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO). As Gurbir Singh, the author of several books on the history of Indian space research, explains, “Nehru really believed in science. He believed that the new nation of India, independent India, should be forged on what he called the scientific temper, the temperament of science.”

Interestingly, India’s space program was not founded as a response to the Cold War, and it had no military undertones. Instead the program was about modernizing India and meeting the needs of society. As Singh explains, “There was a desire for self-sufficiency rather than some sort of hegemony or sense of superiority over other countries. India is probably the only country with a space program which had entirely non-military foundations.” (He adds this has since grown to include military aspects.)

In the 1970s and 1980s, India developed the ability to launch satellites into orbit. These were used primarily for domestic purposes, explains the Guardian, such as mapping and surveying crops, monitoring damage from natural disasters and erosion, and bringing telemedicine and telecommunication to remote rural areas.

ISRO takes off

From the 1990s, when the idea of a mission to the moon was first proposed, ISRO became far more ambitious and globally-minded. This was in direct response to China’s increasing space prowess, argues Singh:

“The moon mission and many other ISRO space programs have been influenced by similar programs in China. In 2003, China had its first human spaceflight success. In 2007, they sent a spacecraft to the moon. They have built their own space stations. So, India has been following in China’s footsteps, just like what happened in the Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union. If China had not gone to the moon, India wouldn't have gone to the moon.”

Section Type: imageOnLeftParagraphToRight

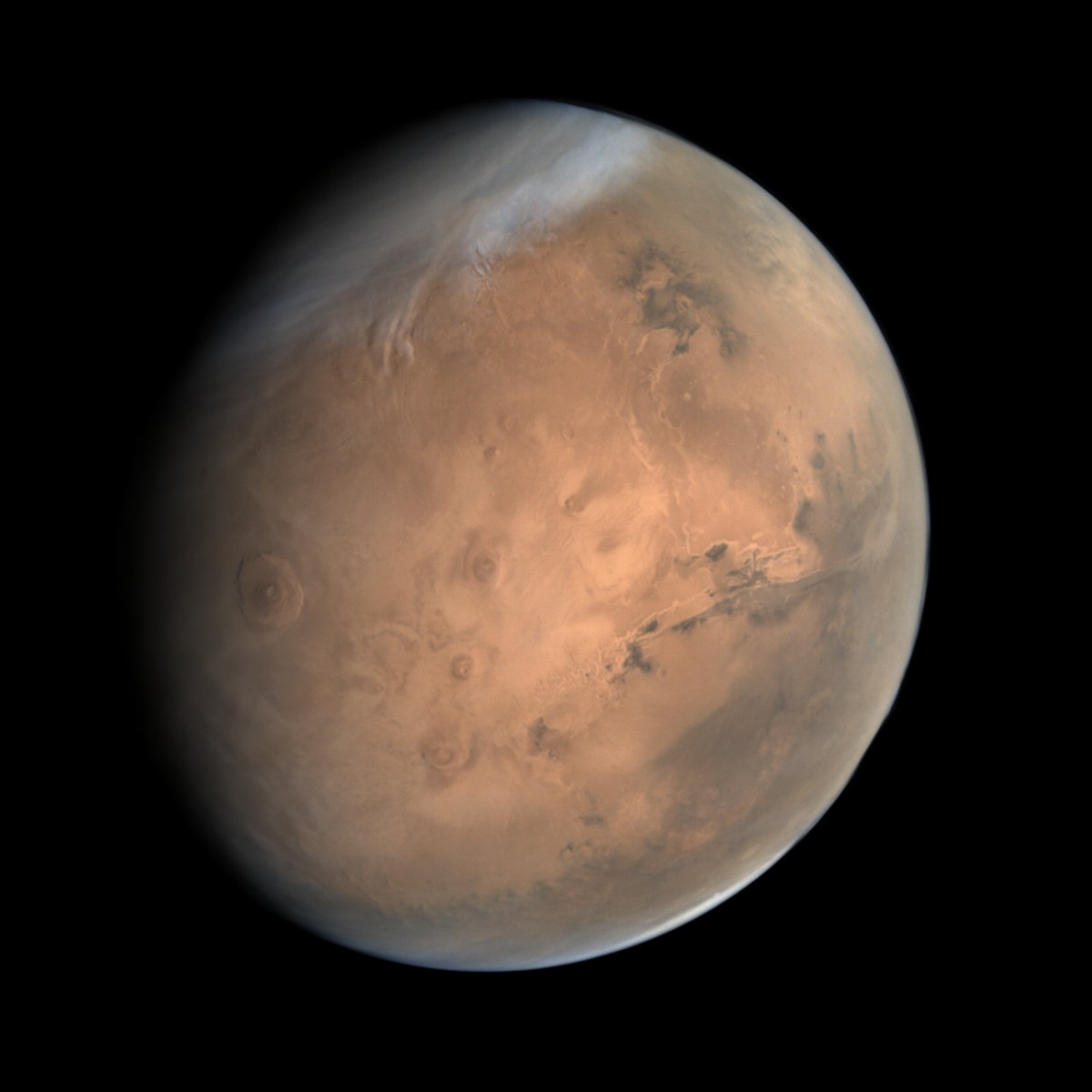

A prime example of this competitive element was India’s 2013 mission to Mars. After missions by Japan and China both failed to reach Mars, India sensed an opportunity. It rushed to put together a basic craft, carrying only five instruments, and successfully landed on the Red Planet. This time there was no denying the flag-waving one-upmanship – it was all very reminiscent of the Cold War.

By the time the moon landing came along in 2023, the political grandstanding had reached new heights. Prime Minister Narendra Modi understood the potential of the space program to both advance his domestic Hindu nationalist agenda and to enhance India’s standing on the global stage.

True-color image of Mars acquired by India's Mars Orbiter mission on October 10, 2014 (Photo: Justin Cowart, ISRO)

The livestream featured a split-screen of Modi, waving a tiny Indian flag, as he watched on from mission control in Bengaluru. (This took some chutzpah – imagine if the mission had failed.) After the landing, he used the platform to address the world: “This success belongs to all of humanity and it will help moon missions by other countries in the future,” he said. “I’m confident that all countries in the world, including those from the global south, are capable of capturing success. We can all aspire to the moon and beyond.”

“Even the sky is not the limit”

It should hardly need pointing out that Modi’s claim that the moon landing “belonged to all of humanity” was somewhat disingenuous. Two months before the moon landing, during a state visit to the White House, India signed on to the Artemis Accords “a set of non-binding principles designed to guide civil space exploration and use” that China and Russia have not agreed to.

During a joint press conference with President Joe Biden, Modi highlighted the importance of the relationship with Washington: “By taking the decision to join the Artemis Accords, we have taken a big leap forward in our space cooperation … even the sky is not the limit.”

NASA, meanwhile, pledged to help India to get humans into space via “a strategic framework for human spaceflight cooperation”. The following year ISRO, NASA, and SpaceX announced that an Indian astronaut, Shubhanshu Shukla, would “serve as a pilot on board Axiom Mission 4 to the ISS … with the express goal of gaining experience for future ISRO crewed missions.”

Looking ahead

Section Type: standardWidthImageS

Image of Vikram lander on lunar surface taken by Pragyan rover on August 30, 2023 (Photo: ISRO)

Historically, space exploration in India was the preserve of the government. This changed in 2020 when – inspired by the contribution of private companies to the American (and to a lesser extent Chinese) space economies – a new law opened the Indian space sector up to private players.

“As a result of new space policies, about 200 startup space companies are now operating in India,” said Singh in 2024. “I think this is where the future of Indian space activities lies: with ISRO helping startups and being supported by startups.”

And as the Economist notes, “It is not only Indian firms that hope to benefit. Some of the world’s largest companies, including well-known names in big tech, are poised to take advantage of Indian expertise in software and data analysis along with low costs.”

India’s space economy is still small – in 2022 it raked in just $10bn, some 2% of the global total – but it is has already overtaken Russia and is expected to grow fourfold by 2030. Space tourism is currently the preserve of US-based companies, but that looks set to change soon: Chinese firm Deep Blue Aerospace has announced plans for “suborbital tourism flights” from 2027.

India, meanwhile, is targeting 2030 for the launch of its first tourist flights. And the plan is for them to be more affordable than most says Pawan Kumar Chandana, co-founder and CEO of Skyroot Aerospace in Hyderabad: “Greater participation by the private sector will activate the economy of scale.”

Section Type: cta

We don’t offer trips to space yet… But we do send travelers to India every year. Check out our most popular tours to this captivating country; then speak to a Destination Expert about crafting your own.

Company

Partners

Copyright © 2025 SA Luxury Expeditions LLC, All rights reserved | 95 Third Street, 2nd floor, San Francisco, CA, 94103 | 415-549-8049

California Registered Seller of Travel - CST 2115890-50. Registration as a seller of travel does not constitute approval by the state of California.