Patagonia isn’t all Alpine lakes and snow-capped mountains; glistening glaciers and abundant forests. In fact there are huge tracts of the southernmost part of South America that wouldn’t even come close to making it into a tourist brochure. These places may not be eminently Instagrammable, but if you take the time to explore them – as filmmaker Carlos Sorín has done – the stories will writhe out, like maggots from the corpse of a beached elephant seal.

Patagonia has always been desolate but in the past this emptiness was tempered by the fact that there was money to be made. Now, not only is the landscape overwhelming and the wind ceaseless (oh, the ever-present wind) but the economic backdrop is also unfailingly bleak.

Obviously the big multinationals are making money from oil, but the oil fields are restricted to certain areas and even then it isn’t a very labour intensive industry. Sheep farming used to be the region’s staple, but a lot has changed since the glory days around the time of the First World War. If you’re not employed by an oil company or in a tourist town like El Calafate (the gateway to the Perito Moreno Glacier) or Puerto Madryn (the town closest to the incredible marine reserve at Peninsula Valdes), day-to-day life is bleak. The young head for the bright lights of Buenos Aires, while the older generation stays at home and get poorer and older. For those that stay life may not be easy, but this doesn’t mean that it stops.

Section Type: standardWidthImageS

Ironically Sorín, who comes from the bustling metropolis of Buenos Aires has found his spiritual home in Patagonia. This quote about his film-making philosophy goes a long way to explaining why he is more comfortable in the Patagonian expanse: “In film I’ve always preferred the gestural to the textual. A look, a silence, a hint of a grin…communicates more forcefully than the rhetoric of the word.” Patagonia is a place of few words.

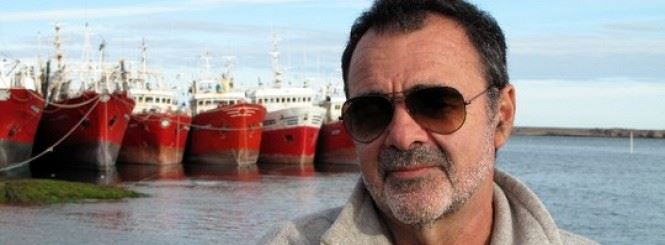

Carlos Sorin

Sorín very seldom uses professional actors (his first film featured Daniel Day Lewis traipsing around Patagonia and was an utter flop), but instead usually casts non-professionals as themselves. People who as he puts it “can be read in their eyes”. Juan Villegas, playing Juan Villegas, is the lead in Bombón: El Perro, an understated road movie about a down-on-his-luck, fifty-something, unemployed divorcee and Bombón the prize dog (a dogo argentino, the legendary Argentine hunting breed) he receives as a gift after helping a woman whose car has broken down on the side of the road.

Juan has been sacked from his job as a petrol attendant, and after first trying his luck at an employment agency and later attempting to sell his (exquisitely crafted) handmade knives, Bombón the dog represents his only hope of making a living. Not that he knows this – it takes a chance encounter with a bank-manager-cum-dog-breeder for the realisation to dawn on him.

The bank manager recognises Bombón’s perfect pedigree and puts Juan in touch with a trainer, Walter Donado (also playing himself). Walter is everything Juan is not: exuberant, optimistic and overweight. There is nevertheless a connection between them, and they agree to enter Bombón into competitions and split the profits 50/50 – a potential lifeline for Juan.

But it won’t come easy. A lot of training and even more driving along the straight, windswept roads of Patagonia (the other star of the show) is required. Through Walter and Bombón, Juan finds renewed purpose and maybe even a little love with a cabaret singer who invites him round for tea the morning after her show.

Historias Minimas was actually released a few years before Bombón, and it was the film which first brought Sorin’s work to world audiences. The similarities with Bombón are many – non-professional actors, minimal dialogue, understated cinematography – but Historias tells three stories not one; intertwining three individual journeys and contrasting them against the epic landscapes of Santa Cruz province.

Don Justo, an octogenarian with failing eyes, hitchhikes to the faraway town of San Julián to follow up a reported sighting of his beloved dog Badface. Roberto, an OCD travelling salesman arranges a surprise birthday cake for the child of a potential suitor, but is forced to hastily convert the football cake he ordered into a tortoise in case he has got the child’s gender wrong. And Maria, brimming with excitement, is on her way to a screening of a local television game show, intent on winning a prize.

Both of these films show real people and tell real stories in the truest sense of the word. The people, the landscapes, the understated cinematography and the gentle humour are what make it impossible to ignore Sorín’s work.

He has since made two more Patagonian films – La Ventana and Dias de Pesca – both of which are worth watching despite not quite reaching the heights of Historias and Bombón.

Copyright © 2026 SA Luxury Expeditions LLC, All rights reserved | 8 The Green, Suite A, Dover, DE, 19901 | 415-549-8049